Dupuytren Disease

Dupuytren disease, known by the medical term “palmar fibromatosis,” bears the name of Guillaume Dupuytren – a French surgeon, and private physician of Napoleon Bonaparte – who famously described its surgical treatment in 1831. It is a genetic disorder most commonly seen in people of northern European descent, hence the colloquial term of “Viking disease”.

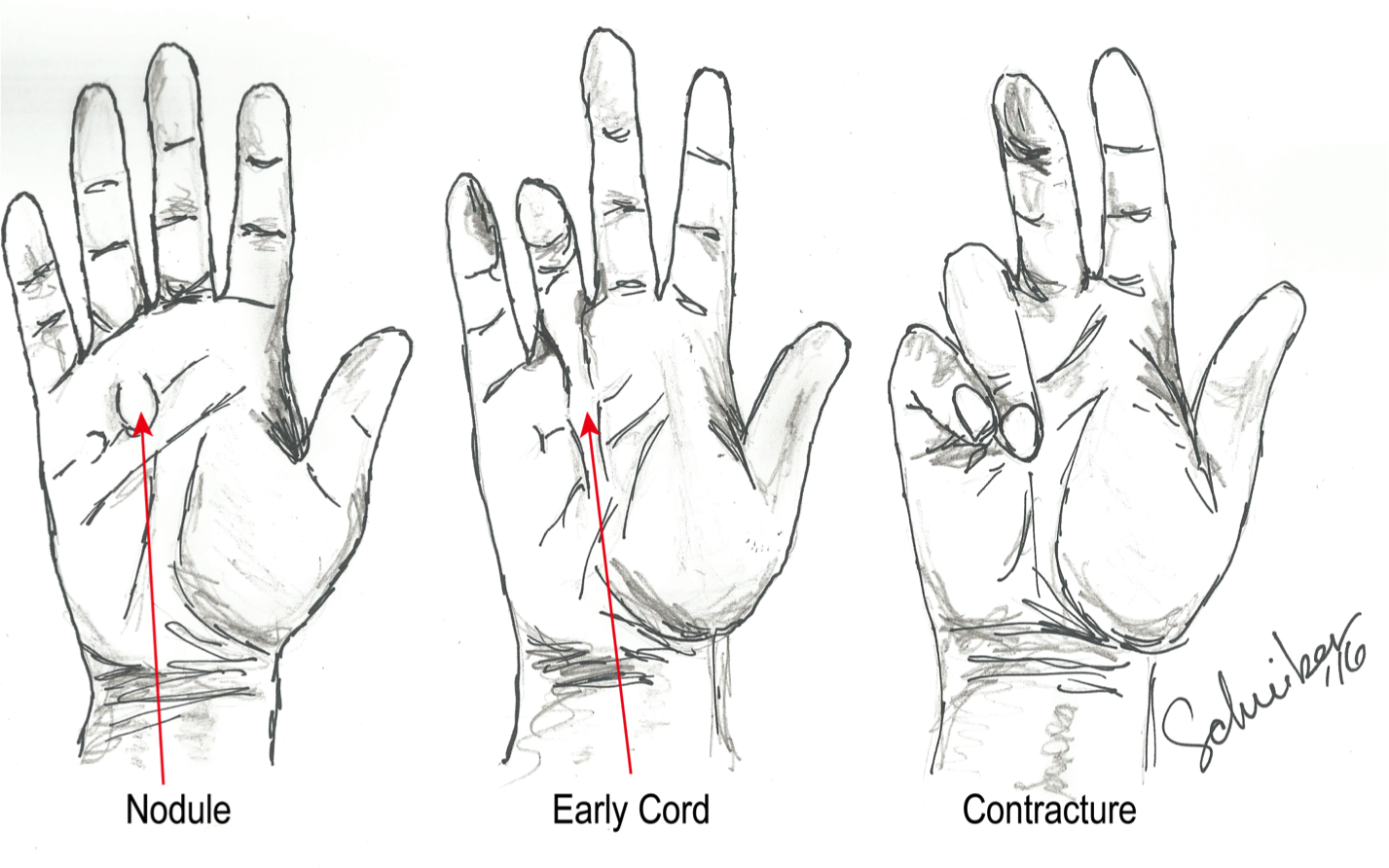

Progression of Dupuytren disease

Patients with Dupuytren disease oftentimes will first notice small nodules or dimples in the palm of their hand. This scar-like tissue can progress and consolidate into “cords” along the palm or fingers. If these cords thicken and shorten, they can cause the fingers to progressively curl up into the palm. This is oftentimes concerning for patients because of either the appearance or the functional limitations that can result. Patients with contractures of their fingers may have a difficult time putting their hands into pockets or gloves, or fully opening their hand to grasp objects such as steering wheels or golf clubs.

Patients often ask what to expect once early signs are seen. Studies following patients with Dupuytren disease over time have shown that it can occasionally worsen, stay the same, or actually improve. Unfortunately, we have no good tools available to predict which one of those three categories an individual will fall into – only time will tell.

There are many treatment options available to patients with Dupuytren disease. While it is always an individualized decision between the patient and physician regarding when to start intervening, typical guidelines include a contracture of the metacarpophalangeal joint (where the finger meets the palm) of 20-30°, or any involvement of the finger joints. Treatment options other than “watchful waiting” include needles or surgery.

Needles can be used to either cut the cord, typically done in an office setting under local anesthesia through the skin, or to inject a medication to digest the cord. One of the notable advancements in the field of hand surgery over the past decade was the FDA approval of a drug called Xiaflex. This medication is a collagenase, meaning that it is an enzyme that digests collagen, the scar-like material that makes up the cords. Xiaflex is injected into the cord, and the patient returns within one week to have the finger stretched back out to a straightened position. Oftentimes, patients will feel the cord pop or snap before they actually come back for a stretching, such as when lifting a bag of groceries. In the initial Xiaflex study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the average patient had about a 75% improvement in their contracture after treatment. Advantages of this technique include its minimally-invasive nature, but there are small side effects seen, such as itching, bruising, discomfort and occasional skin disruption during the stretching procedure. Five-year follow up results of the early patients were recently published and showed that the Dupuytren disease can occasionally come back. This occurs more commonly when it involves the finger rather than the palm.

The tried-and-true treatment option, as first done by Guillaume Dupuytren himself, involves removing the scar-like collagen tissue surgically through an incision along the palm. Regardless of treatment type, patients are typically given a splint to wear at nighttime for the first 4 months after treatment, to prevent recurrence, but will typically have unlimited use of the hand during the daytime. Dupuytren disease tends to be unpredictable, but many treatment options are available if it seems to be progressing. If you are interested in discussing your options or having a baseline examination recorded, which can then be followed over time, please call 919.863.6808

Dr. Schreiber is a board certified orthopedic surgeon specializing in hand, wrist, and elbow conditions. Dr. Schreiber practices at the Raleigh Orthopaedic Clinic in Raleigh, North Carolina.